What Are People For?

Adapted from Becoming Whole: Why the Opposite of Poverty Isn’t the American Dream, by Brian Fikkert and Kelly M. Kapic, pp. 43-52. Used by permission of Moody Publishers.

If we are serious about our efforts to address the root causes of material poverty and see real change in the lives of people in our communities and around the world, there is a key question that we often fail to ask first. What are people for? How we answer that determines so much about what we think of when we think of material poverty and what we will try to do when we seek to help those struggling through it.

What Is a Human Being?

No single Bible verse outlines precisely what it means to be human. Through the centuries, therefore, Christians have looked to the Scriptures as a whole to discern the nature of who we are.1 Understanding what it means to be human matters immensely, for to truly help anyone, we need to understand how God made us all.

The Human Being as Body and Soul

According to Scripture, our bodies really matter, but we are not merely physical. For Christians, the word soul has often been used to signify this something more than the physical. The Bible indicates that humans continue to exist even beyond the experience of physical death (Matt. 10:28; Luke 12:4-5; Rom 8 35-39; Rev. 20:4). When a person dies, their body may be lying on a bed before us, but we sense they are no longer with us. Their life or soul is gone. That is partly why we ache so deeply when loved ones take their last breath. Their bodies are still with us, but they are no longer present.

The Bible presents a holistic view of being human, so while it’s helpful to distinguish between the body and soul, we should avoid separating them. A key Hebrew word (nephesh) commonly translated as “soul” literally means “throat” or “neck.” This nephesh represents our life, our very being. Interestingly, the Bible uses earthy language in reference to our souls. Why? Because you can’t easily separate the body and soul. Similarly, the Hebrew word leb, which the Bible often uses to refer to the inner human being, is commonly translated as “heart,” a physical organ! The body and soul are not easily disentangled in Scripture.

This has huge implications for the design of our poverty alleviation ministries. People are whole people. So, partial solutions that address either the body or the soul will not work as well as solutions that address both the body and soul. The effectiveness of an after school tutoring program for low-income children might be hindered if the children are so hungry that they cannot pay attention to the lesson. And a job training program that increases a husband’s income and physical well-being without addressing his spiritual condition could simply create a workaholic whose mental health deteriorates over time. The body and soul are highly interconnected. In fact, they aren’t really two different things, but refer to two aspects of one person. And together, these two aspects capture the fullness of the whole being.

Theologians have sometimes found it helpful to speak of three facets of the soul: the mind, affections, and will. For the purposes of this book, we define these terms as follows:

- The mind points primarily to our understanding or rationality;

- The affections focus our attention on the importance of desire, emotion, and longings;

- The will highlights the importance of human agency, what we decide to do or not to do.

While distinguishing between these three aspects can be useful, they should not be thought of as distinctly separate components of the soul. Rather, the mind, affections, and will are different characteristics of one whole human soul, which is itself deeply integrated with the body. Sadly, sometimes churches or denominations distinguish too sharply between these features, pitting them against one another in problematic ways. For example, one church values the mind, while another highlights the power of emotions; one community concentrates on stimulating the will to action, while another emphasizes emotional self-control; one denomination emphasizes material prosperity, while the other acts as though only our souls matter. But we should never pretend that only one aspect of the human person is important. The Bible assumes that all aspects of the human being are highly important and deeply integrated, and so should we.2

In fact, the three features of the soul are so interrelated that the Bible uses the word heart (leb) to describe all of them. In Scripture, heart can refer to our minds as well as our emotions, to our actions as well as our desires. Hence, it’s not surprising that Scripture commands us to pay special attention to the state of our hearts: “Above all else guard your heart [leb], for everything you do flows from it” (Prov. 4:23; see also Matt. 12:35). This verse doesn’t merely state that we should guard our hearts so we can go to heaven someday, but that everything we do in this world—the way that we work, eat, play, date, raise kids, vote, spend, give—flows from our hearts. Whatever our hearts love most—the thing that commands the ultimate allegiance of our minds, affections, and wills—determines our actions. Just as love is at the heart of the triune God, so love is at the heart of human beings. And just as the creation flows out of God’s love, so too our actions flow out of what we love.3

As Christian philosopher James K. A. Smith has emphasized, this understanding of human beings starkly contrasts that of Western civilization, which tends either to doubt the existence of the soul or reduce it to the mind (think of Descartes’ statement “I think therefore I am”). Although the ability to think and reason is vitally important, human beings are primarily lovers.4 We are driven by what our hearts—our minds, wills, and affections—love most. Hence, the way to a person’s heart is to capture their imaginations (minds), move their emotions (affections), and challenge their actions (wills). While we can play a role in shaping people’s hearts, ultimately such transformation requires the miraculous work of a sovereign God.

The Human Being as a Relational Creature

Because the heart is at the center of the human being, humans are necessarily relational creatures; love must be expressed towards someone or something. As creatures who reflect the triune God, human beings are hard-wired for relationship. We are not created to live as autonomous individuals. In fact, when humans live in isolation from others, the effects are devastating.5

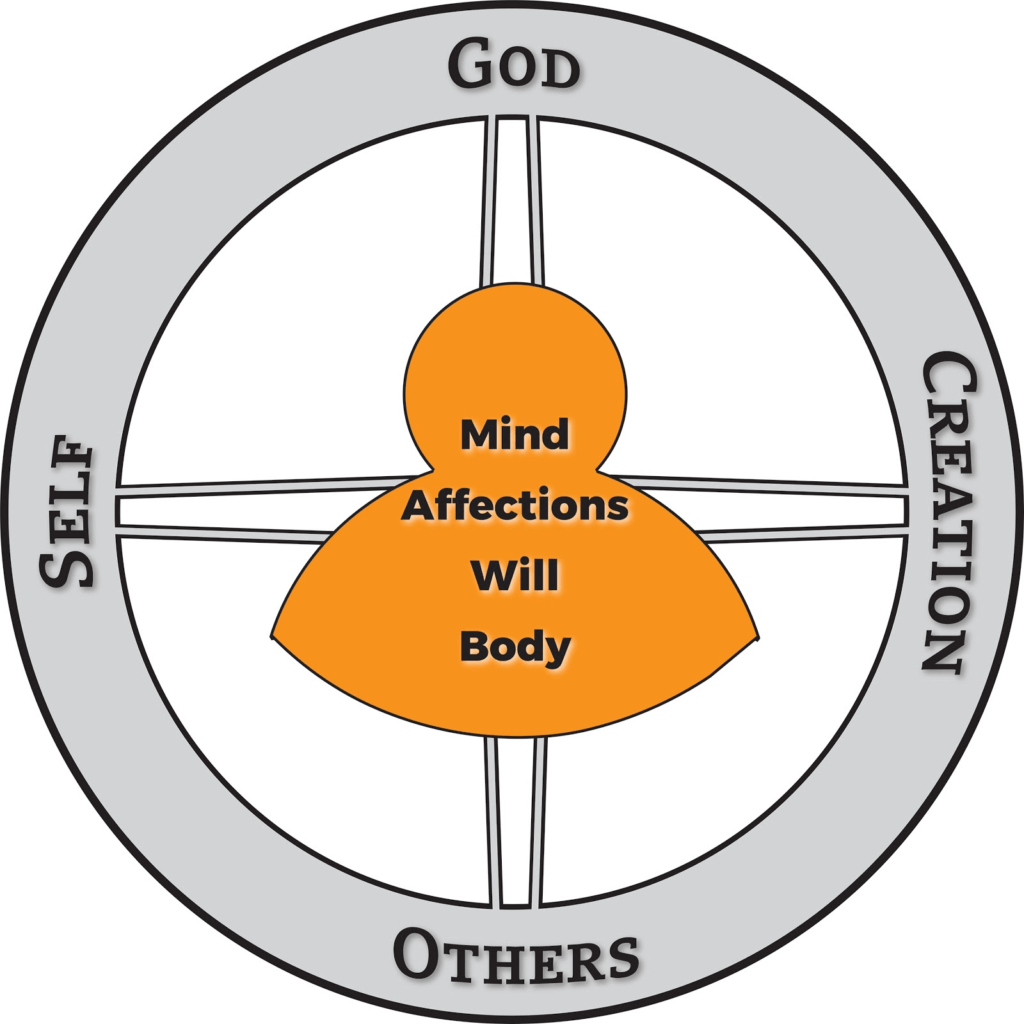

Theologians regularly point to four fundamental human relationships emphasized in Scripture: relationships with God, self, others, and the rest of creation (see Deut. 6:4-6; Gen. 1:26-28).6 The relationship with God is central, as it is the foundation for the other three. Part of the way that we both love God and experience His love for us is in our relationships with self, others, and the rest of creation. When we hold our little girl’s hand as we walk along the beach, for example, we express the love of our heavenly Father to her and experience His love back to us in her adoring eyes. Our relationship to God is integral to how we experience the other three relationships.

It’s important to understand that the nature of these relationships is not arbitrary. God has designed them to work in a certain way, and humans only flourish when we experience these relationships the way God intended. Further, these four relationships are highly integrated with a person’s body and soul so that the human being is a mind-affections-will-body-relational creature.

Adapted from Brian Fikkert and Russell Mask, From Dependence to Dignity: How to Alleviate Poverty through Church-Centered Microfinance (Grand Rapids, Zondervan, 2015) p. 83.

No analogy is perfect, but we can illustrate some aspects of this mind-affections-will-body- relational creature through the image of a wheel (see below). The boundary of the human being is not the hub in the middle—the person’s body and soul. Rather, the human being is the wheel as a whole, including both the person’s body and soul (the hub) and their relationships (the spokes). Remember, the relationship with God is more foundational than the other three, so that spoke is more important than the others.

Each part of a wheel impacts all the other parts. If one spoke is misaligned, enormous pressure will be placed on all the other spokes and on the hub itself, and they all will eventually bend or break. For example, when a man loses his job, this results in far more than the loss of income, as it entails a broken relationship with creation. As the spoke connecting the hub to creation is bent or broken, additional pressure will be put onto the rest of the wheel, onto the person as a whole. The other spokes will weaken, as there will likely be marital stress (relationship to others) and a low self-image (relationship to self). And the hub itself will be damaged, as the person may experience mental and physical health issues.7

A wheel is shaped by both internal and external forces.8 Even a strong wheel that hits a pothole can end up with bent spokes and a damaged hub. Similarly, human beings are shaped by both internal and external forces. Internally, our mind, affections, will, and body play a huge role in determining the nature of our relationship to God, self, others, and the rest of creation. However, external forces shape those relationships as well. For example, the unemployment experienced by the person above could have been caused by the present economic crisis resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, leaving him and millions of others without a job no matter how much they desire to work. Their relationship with creation was broken. And this broken relationship with creation impacts their other three relationships as well as their minds, affections, wills, and bodies. Human beings are highly integrated, mind affections- will-body-relational sorts of creatures that can be impacted by both internal and external forces.

The Goal of Poverty Alleviation

So what is the goal of life? From a biblical perspective, the goal for all humans—including the materially poor—is to be what God created us to be. And as we have seen, human flourishing is to be a well-balanced “wheel,” using our minds, affections, wills, and bodies to enjoy loving relationships with God, self, others, and the rest of creation.

So how is this borne out in our poverty alleviation ministries? There are many, many ways, but let’s consider three here:

- If a woman walks into your church, asking for help with her electric bill, her behaviors both before and after that moment will fundamentally be driven by what she loves. Thus, if her need for financial assistance is a result of her own behaviors—and it might not be9—then effectively helping her material condition requires addressing her heart condition. There are no shortcuts or alternatives; her heart is at the center of her personhood and drives her behaviors.

- Second, as you attempt to minister to this person, you must treat her as an integrated whole. Unfortunately, some poverty alleviation efforts reduce this woman to her mind, believing that education alone will solve her problems. Others concentrate on her will, using “carrots and sticks” to spur her to action. Still others focus solely on the body, pouring all their attention into meeting immediate physical needs while failing to appreciate the emotional and spiritual challenges that are also present. Even secular poverty alleviation experts recognize that these partial solutions often fail, because people are multifaceted creatures with multifaceted problems.10

- Third, your own heart drives your response to this woman. Do you create a narrative about her that belittles her so that you don’t feel obligated to help her? Do you create a story in which your possessions are indicative of your moral superiority when, in fact, both her story and yours are far more complicated? What will be key, both for the woman and for those responding to her, is love. And central to this love is discovering the biblical truth that God first loved us, well before we loved Him.

There is so much more that can be said, but this biblical perspective on the nature of human beings is foundational to every other aspect of poverty alleviation that we promote as an organization. Until we grasp the wonder of who God created us to be, we are likely to do unintentional harm as we try to help others.

- See Kelly M. Kapic, “Anthropology,” chapter 8 in Christian Dogmatics: Reformed Theology for the Church Catholic, Michael Allen and Scott R. Swain eds., (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2016), 65-93; Richard Lints, Identity and Idolatry: The Image of God and Its Inversion (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2015); Anthony A. Hoekema, Created in God’s Image (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1986), 68-73.

- It is not that we are against more contemporary psychological language and more technical discussions of the human person, but we think that ancient and biblically saturated ways of speaking provide sufficient guidance as we wrestle with what it means to be human and how we should treat one another.

- See James K. A. Smith, Desiring the Kingdom: Worship, Worldview, and Cultural Formation, vol. 1, Cultural Liturgies (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2009), 51-52.

- Ibid., 75.

- See, for example, studies on the harmful effects of solitary confinement and loneliness.

- For example, see Hoekema, Created in God’s Image, 75-111.

- See Brian Fikkert and Michael Rhodes, “Homo Economicus versus Homo Imago Dei,” Journal of Markets and Morality 20, no. 1 (Spring 2017): 101-126.

- Lints, Identity and Idolatry, 18-19.

- There are many situations in which a person’s own behaviors are not the primary cause of their material poverty (such as in cases of abuse, neglect, injustice, or oppression), in which case their own heart condition is not the only key to alleviating their poverty. Further, even if someone is fully responsible for his own predicament, that does not automatically imply we should not help. In most cases, there are multiple causes for poverty—some that are internal to the person and some that are external—requiring careful analysis and multifaceted approaches.

- See, for example, Robert Chambers, Rural Development: Putting the Last First (London, UK: Longman Group, 1983), 10-39.