Stewarding the King’s Gifts to Advance His Kingdom

Adapted from Brian Fikkert and Kelly M. Kapic, A Field Guide to Becoming Whole: Principles for Poverty Alleviation Ministries (Chicago: Moody Publishers, 2019), 75-79.

Every poverty alleviation effort—whether it comes from a local church, a parachurch ministry, or a secular nonprofit—includes three groups of stakeholders: donors, the ministry employees (and long-term volunteers), and the materially poor people the initiative hopes to serve.

These stakeholders typically have very different educational, professional, socioeconomic, and cultural backgrounds that can make it difficult for them to even understand each other, much less collaborate. And to make matters worse, these stakeholders have often internalized very different stories of change that they may not be aware of. Satan loves to exploit these differences, sowing seeds of distrust within the household of faith and undermining the advancement of Christ’s kingdom.

Let’s unpack this.

Different Personalities, Attitudes, and Expectations

Many donors are businesspeople or have at least worked in the for-profit sector, a world that emphasizes efficiency, productivity, metrics, accountability, rationality, and technological mastery. Because donors have been financially successful, they are typically heroes in their cultures: they are the successful ones; they have won the game of life. So when these brothers and sisters enter the space of poverty alleviation, they tend to enter with confidence and optimism, expecting to experience the same success in this space that they have experienced in the for-profit sector. And they tend to automatically assume that the same organizational model that operates in the for-profit world, or some facsimile thereof, should be used in the ministry world—the profit-making business.

Materially poor people might as well be living on different planets from the donors. They often feel unable to control their individual lives, much less their environments. Technological mastery of the natural world? They’d prefer something to control demons. Getting an advanced degree to climb the corporate ladder? They’d be happy if their kids’ teachers would just show up to school every day. In contrast to the cultural affirmation that donors are accustomed to, the message to the materially poor is that they are inferior, unintelligent, and unwanted; they are the losers in the game of life. So, when these materially poor brothers and sisters learn about a new poverty alleviation ministry, they tend to be pessimistic about the chances that it will work for people like them.

In between these two groups are the ministry staff. Their educational backgrounds and professional experiences tend to be in social work, psychology, healthcare, teaching, missions, theology, and community development—all of which tend to have a more relational approach to life than the business world. Indeed, the personality profiles of many ministry staff are often at opposite ends of the spectrum from that of their largest financial supporters. While the ministry staff typically do not receive the same social accolades as wealthy donors, they are at least respected by the larger culture for their technical expertise and “sacrificial service.”

The space of poverty alleviation entails a collision between these three very different groups of people. How can these differences be managed?

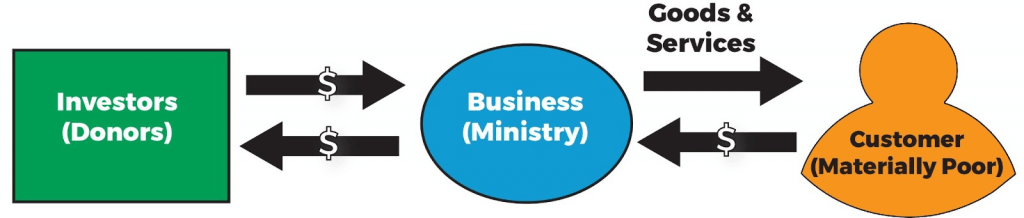

Revisiting the Business Model

The business world has an answer: The for-profit business enterprise aligns the different backgrounds and interests of investors (donors), the business (ministry), and customers (materially poor people). As pictured in the graphic below, in the business world, investors put money into the business, expecting a financial return. The business uses that money and other resources to produce goods and services that the customers want, receiving money from those customers in return. The revenues from the customers are used to pay the employees and to reward the investors. In this world, it doesn’t matter that the investors, employees, and customers are all very different from one another, because the business model creates alignment between these different parties. Customers get what they want: goods and services. The employees get what they want: jobs that pay them an income. And the investors get what they want: a financial return on their investment.

While there are very important lessons that can be gleaned from the business model, the model breaks down in many respects in the non-profit space. Because the customer (the materially poor person) is typically not paying for the vast majority of goods and services they receive from the poverty alleviation ministry, there is nothing to guarantee that the ministry will actually provide them with what they want at a high quality. Indeed, the financial incentives are for the ministry to serve its donors, because they are the ones who are paying for the employees to have jobs. Hence, while the customer is king in the business sector, in the non-profit sector the temptation is for the donor to become king, because they are the ones who are paying the bills. In essence, the donor becomes the primary customer. As a result, what donors believe materially poor people need is what materially poor people are going to get. And in the process, the donors’ story of change—whether it be Western Naturalism, Evangelical Gnosticism, or something else—gets imposed onto materially poor people.

This problem is exacerbated in the context of church-based ministry, because the church is simultaneously both the ministry and the donor. For example, think of a short-term mission trip. Those going on the trip are the “ministry,” but they are also the ones paying for the ministry (along with their friends and relatives). In business terms, we would say that the employees have become the customers! And because the customers are kings, what they want is what poor people are going to get. If the short-term team believes that materially poor people in Tibet need Frisbees, then Frisbees it is!

Toward a Solution

What to do?

To solve these alignment and incentive problems, many donors, businesspeople, and non-profit leaders are trying to bring principles from the business world into the non-profit space. In particular, the exploding social entrepreneurship and social innovation movement is giving birth to a host of new and creative ways to provide materially poor people with the services they really want on a much larger scale. This movement has much to teach us, for it has tremendous insights.

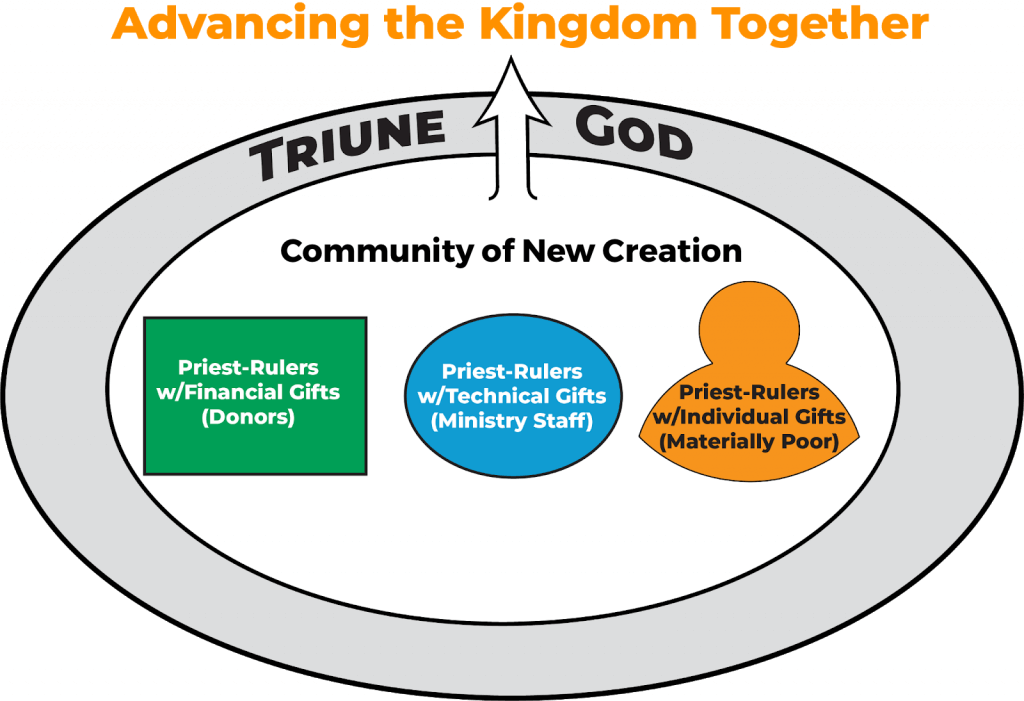

That said, we need to keep God’s story of change at the center: the triune God and His people are dwelling in community with one another. The goal of our poverty alleviation efforts isn’t just that people are no longer materially poor. Rather, it is for people to experience human flourishing through serving as priest-rulers in God’s kingdom, using their mind, affections, will, and body to enjoy loving relationships with God, self, others, and the rest of creation.

Of course, though, all the stakeholders of any ministry are people in process, growing toward this goal, even as they experience both the “now and not yet” of God’s kingdom. As such, all the people in this community—including donors, ministry staff, and materially poor people—are called and empowered to use their gifts, not to seek their own interests, and to advance Christ’s kingdom together. This reality, seen in the graphic below, should be at the forefront of our minds.

There is so much more that needs to be said on this topic. And so much more needs to be done in order for financial resource partners, ministries, and materially poor participants to become better aligned and to become mutually accountable to one another. But an important first step is for all the stakeholders to agree that they are all working toward God’s story of change, which is central to the ministry of the Chalmers Center.

In a subsequent post, we’ll give some concrete recommendations to each group of stakeholders to start living into God’s story in their respective roles.